- Home

- Home

- Links

- Back Issues (PDF)

- A Career in Pilotage

- About The Editor

- About the UKMPA

- Contact the Editor

- Articles

- Contents

- Features

- History

- Incidents & Investigations

- Pilot Ladders

- Pilotage News

- Reviews

- Technical and Training

- The latest issues: 327

The Pros and Cons of the Con – Time to call a Truce

William Hargreaves (Southampton)

There has over the last few years been considerable discussion about the role of the pilot, not least in the pages of ‘Seaways’. Does he or she have conduct of the vessel, or is the pilot merely an adviser? By definition, a debate has two sides: us and them, pilots and bridge teams.But it shouldn’t be adversarial at all. Pilots and bridge teams are actually on the same side. What both parties want is a successful act of pilotage with the minimum amount of paperwork, hopefully conducted in a pleasant and supportive environment with a mutual respect for each other’s professionalism.

The most familiar definition of a pilot is from the UK Merchant Shipping Act of 1894: ‘pilot shall mean any person not belonging to a ship who has the conduct thereof’. But this definition was taken verbatim from the 1854 Merchant Shipping Act. 1854 was the year of the Crimean War and the infamous cavalry Charge of the Light Brigade. In London that year 10,000 people were killed in a cholera epidemic. Life was very different then. It was also the golden age of the clipper sailing ships. No engines, no electronics, open bridges and, one would suggest, a rigid and hierarchical command structure. Would a junior officer on a clipper ship have challenged the actions of a pilot?

The 1854/1894 definition of a pilot is readily understood and accepted by the English-speaking world. The UK Merchant Shipping Act of 1894 or its interpretation not only applied in the UK but in many other countries of what was then the British Empire. But what of other cultures? How do they interpret the role of the pilot?

In Greece, for example, the Code of Public Maritime Law (*1) states that the ‘suggestions and directions provided by the pilot to the master are of an advisory nature’. Perhaps that explains why, on a Greek-manned bridge, every order from the pilot is repeated by an officer. It’s not an order until the master or his deputy has repeated it. While the repetition of the pilot’s orders may be considered mildly irritating, the practice must be respected by the pilot.

Under the Russian Merchant Shipping Code (*2) the ‘master may charge the pilot to give direct orders to the helmsman’. The inference is that the master doesn’t have to. Russian law also defines the pilot as a representative of the state. Which is a reminder that, under UK law, the 1894 definition of a pilot is incomplete. Today’s pilot is required, under port state control legislation, to report any defects of the vessel. The pilot’s legally defined role has and will continue to evolve.

The 1894 definition of the pilot has been challenged in the courts. But the judgments will be influenced by the standards and social norms of the time. For example, two years before the 1854 Merchant Shipping Act, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the pilot was the ‘temporary master’, the ‘master ad hoc’.( *3) Today it is highly unlikely that anybody would accept that the pilot retains such an exalted position not even the American pilots themselves. In a statement released in 1997, the American Pilots Association succinctly summed it all up: ‘navigation of a ship (…) is a shared responsibility between the pilot and the master/ bridge crew’. (*4)

While it may be legally dubious, the role of the pilot is also subject to individual company interpretations. For example, an Irish shipping company has a sign in the wheelhouse which states that ‘the pilot is onboard to provide advice only’. This reflects the entry made by many an officer in the deck log book: TMO & PA (To Master’s Orders and Pilot’s Advice). While this may be true of some legislations, under UK law it is incorrect. An authorised pilot in the UK is not an adviser. He or she is not allowed to be. The UK pilot gives orders and has conduct of the vessel.One of the legal challenges was the 1907 case of the Tactician. The Tactician while under pilotage collided with a vessel at anchor on the Thames. The pilot had incorrectly thought he was looking at the sternlight of a vessel underway. (The bridge crew had correctly identified the light as an anchor light but failed to inform the pilot, an example perhaps of a rigid and hierarchical command structure.) In his judgment Lord Alverstone noted that ‘all directions as to speed, course, stopping and reversing and everything of that kind are for the pilot’ (*5) . Significantly, he went on to say that ‘the pilot is entitled to the fullest assistance of a competent crew’.

Despite this interpretation of the law, there are documented examples of the captain or his deputy manoeuvring his or her own vessel. For example, an American accident report stated that ‘the master confirmed to investigators that a pilot had never docked the vessel while he served as master'(*6). Similarly, ‘by mutual agreement between the Association of Maryland pilots and the passenger vessels berthing at the cruise terminal, the conn was shifted from the pilot to a ship’s officer for the final approach and docking’. (*7) All pilots know that the master of the small coaster will often berth or unberth his or her own vessel. A similar situation occurs on large cruise ships, unless tugs are involved. On the coaster the transfer of the controls is generally informal, something along the lines of ‘I’ve got it now, pilot.’ On the cruise ship it tends to be much more formalised with multiple repetitions of ‘The captain has got the con.’ A Southampton pilot stated that, in accordance with the law, he never gave the captain the con; rather he tells the captain that ‘If you would like to do the manoeuvre I will monitor you and tell you if I’m not happy.’ As he stated, he’s still met by a barrage of ‘The captain’s got the con!’ Regardless of whether it is called manoeuvre, control, conduct or similar term, the reality is that the captain or the deputy has control of the speed, course, stopping and reversing of the vessel. But the pilot, by law, cannot voluntarily relinquish the con and therefore the pilot must monitor the captain’s actions, and, in accordance with the law, continue to give instructions or orders about the direction and speed of the vessel.

Should the pilot, or harbour master, have a problem when a ship’s staff handle their own ships? Bridge Resource Management (BRM) has been defined as ‘a team approach, where all available materials and human resources are used to achieve safe operation’. (*8) Is not the pilot making best use of the resources available? The pilot doesn’t, for example, micromanage the helmsman. A course is given to steer and as long as the heading is maintained and excessive helm is not used then the helmsman is left to get on with it. Allowing the master to berth his or her own ship is often the best use of resources. While pilots are familiar with azipods, few have had the extensive training or familiarisation that the master will have had.

The UK Merchant Shipping Act definition of a pilot was written over 160 years ago. The judgment from the Tactician is more than one hundred years old. Ship propulsion systems and bridge team management techniques were very different then. Yet the legal advice is that the pilot must never relinquish the con. A pilot had a berthing incident very recently and when he reported the incident to his insurers they asked if the harbour master was aware that the ship’s master was performing the unberthing manoeuvre. In such circumstances, the legal advice is that a VHF call should be made to VTS reporting the fact. But pilotage is about building up a sense of trust between the master and the pilot, and consequently the pilot may be reluctant to make such a call. Is it about time the definition of ‘conduct’ be amended to take into account modern practice?

The act of pilotage can usually be divided into two stages. The passage through the district and the berthing or unberthing. It has been suggested that passenger vessels would prefer to keep the con throughout both stages of the pilotage. Ignoring the legality of such a move, can it be described as sensible? Is it the best use of resources? As one academic has put it, ‘Pilots are highly experienced process controllers with highly developed models of the system they are controlling and the areas in which they work.’ (*9) Before a pilot is licensed for the largest vessels to use the port, he or she will have had many years training and will have built up a wealth of experience not only about courses and distances but also about the other users in the district and what might be expectedof them. At a presentation given in Cork in 2018, attendees were told that on modern cruise ship bridges the ‘system focuses on instrument navigation backed up with visual and pilot clues. Walking round the cockpit-style bridge is not encouraged …’ (*10) But in a pilotage area where, for example, there can be literally hundreds of pleasure craft the visual clues and the experience of the pilot must take priority.

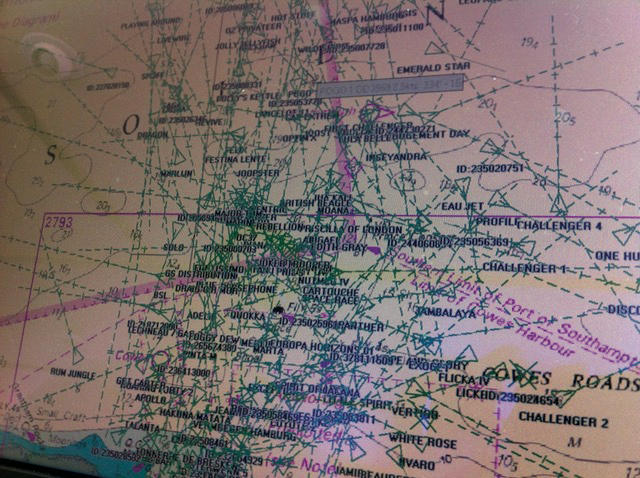

It is interesting how a term can evolve over time. For the master of the 1854 clipper ship instrument navigation meant a sextant, leadline and compass. For the 21 st century navigator the term ‘instrument navigation’, as used in the quotation above, will refer to radar, ECDIS, AIS, Doppler, etc. There is no doubt that without such technologies it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to manoeuvre the largest vessels in ports today. Indeed, many ports require high precision portable pilot units to be used for the pilotage of the largest vessels to access the port. But GPS can be jammed or spoofed. In April 2019, the US government warned against possible errors due to a ‘week number rollover event’. Navigators today only occasionally crosscheck the ECDIS with visual or radar fixes. Pilots’ familiarity with their district, their positional awareness and their ability to recognise that the vessel is swinging too quickly or too slowly, means they are an invaluable resource which must be an integral part of the planned pilotage.

In the article ‘Bridge Team and Pilot Cohesiveness’ (*11) the author stated that the ‘goal, with proper training and the pilot’s agreement, is to be able to drive a ship into port using our track control system, (…) the bridge team are in monitoring mode’. One can’t fault the ambition. An autonomous ferry has already travelled from berth to berth in Finland, albeit in strictly controlled conditions. Humans make mistakes so let’s take the humans out of the pilotage. Though, since humans have designed the system, planned the passage, and set the parameters, you can never really take the human out of the system. Track pilot is a case in point. In track mode, the machine follows a predetermined track. However, as one pilot mentioned in a private email: ‘We have had one very difficult Captain (…) who is very insistent that he would like to use Track Mode with just one track that can be used for every arrival and departure (i.e. making no allowance for tide or wind, inward or outward).’ Or other traffic. IMO have been developing the concept of eNavigation over a number of years. The objective is that there will be data links between all commercial vessels. Legislation may in the future allow for shore-based pilotage. Then it will be possible for the VTS to link with and coordinate all such vessels in its district; though it is unlikely that every yacht and jetski will ever be part of such a system. In the meantime, as the UK Department of Transport has stated: ‘A pilot’s primary duty is to use his skill and knowledge to protect ships from collision and grounding by safely conducting the navigation and manoeuvring whist in pilotage waters.’ (*12)

There are roughly 53,000 internationally trading vessels. The vast majority enter and leave port without incident. Not that this is a reason for complacency among pilots. One of the conclusions after the grounding of the CMA CGM Vasco de Gama was that ‘the master, the assistant pilot and the bridge team became disengaged from the pilotage process and allowed the lead pilot to become an isolated decision maker and a single point of failure’. *(13) Whenever there is an incident whilst under pilotage, the conclusions of any investigation will usually highlight shortcomings between the pilot and the bridge team. In this age of mass surveillance, the pilot’s every movement, every decision, and every word is being recorded on at least one piece of electronic equipment: the VDR, ECDIS, PPU, VTS, cameras, possibly even mobile phones. An American pilot stated last year that there had been an incident where the US Coastguard seized a pilot’s fitness tracker so they could study his sleep patterns. Possibly the story is apocryphal, but it shouldn’t surprise anybody who works on ships.

As a consequence, it is incumbent on all pilots to ensure their conduct onboard is exemplary. The bridge team must be engaged, the master-pilot exchange must be comprehensive, and the pilot must ensure that his intentions are clearly understood. ‘Thinking aloud’ is a comparatively recent term for what has always been good practice. The VDR, and especially the bridge microphones, should be considered the pilot’s best friend and most reliable witness. Pilotage is under the spotlight as never before. Australia and New Zealand have placed marine pilotage on a watchlist, expressing serious transport concerns and highlighting a continuing theme of poor Bridge Resource Management, (BRM). In the UK, both the pilot and master of the City of Rotterdam were prosecuted for conduct endangering the ship. It didn’t matter who had the con, both the pilot and master were considered to be responsible to each other for ensuring that the principles of BRM and best navigational practice were adhered to.It is a cliché, but true nonetheless, that we live in litigious times. Even if the bridge team is totally disinterested, which – as pilots know – still happens all too frequently, pilots must ensure that their conduct is robust enough to withstand the closest scrutiny. If the pilot is that single point of failure then he or she will have a strong defence if, despite their best efforts, it can be seen on the VDR that the bridge team did not fully engage with the pilot. But should the pilot really be piloting such a vessel? Pilots generally are can-do people who want to get the job done. But perhaps pilots should be more concerned about protecting themselves from possible prosecution. If the ship doesn’t have a supportive bridge team then in accordance with international convention and port state control legislation it should be considered substandard and put to anchor. (On the 8 th March 2019 the English Admiralty Court handed down a judgment that ‘defective passage plans render a vessel unseaworthy’.) (*14)

As mentioned, there are approximately 53,000 internationally trading vessels. Of these, 314 are (*15) cruise ships. Yet the controversy about who has the con was triggered by this small sector of the industry and specifically the new bridge practices developed by Carnival at its training facilities in the Netherlands. While pilots have criticised the practice of repeating every order as a question to be answered with a yes, this is the company culture, and, while it may be considered mildly irritating, the practice must be respected by the pilot. Carnival’s own fleet orders state that ‘a pilot strengthens and supports the bridge team with local information, knowledge, risk assessment and expert navigation’ (*16) (CSAF038). However, while the pilot is there to support the bridge team, ‘masters and bridge officers have a duty to support the pilot’ (IMO Resolution A.960). The pilot should be integrated with the bridge team, but as an equal partner and not subservient to the rest of the bridge team. The design of some bridges puts the pilot literally to one side of the conning position, meaning it is difficult to integrate with the bridge team. On such vessels, the pilot usually has an allocated radar and VHF but other information such as the rate of turn indicator is not easily seen. (I tend to stand behind the navigator and co-navigator where I can see all the relevant information.) The pilot and the bridge team must have access to the same navigational information. ‘No team can work cohesively unless they share a common understanding of the goal. Within BTM, this principle is often described as the development of a shared mental model.’ (*17)

Of course, contrary to popular myth, pilots are not superhuman. The pilot who steps onboard may be fatigued, bereaved, depressed or have other personal worries and concerns. Although the pilot needs to be at the centre of things it does not mean that they will have correctly assimilated all the information in front of them. For example, an investigation into a collision between three vessels concluded that ‘the pilot’s effectiveness was reduced due to his heightened workload, frustration and increasing stress’. (*18) And the master was unable to properly monitor the pilot because he ‘had not gained sufficient information about the pilot’s intentions for him to check progress against the plan or to ensure the safety of his vessel’. Interaction between the master and pilot had been minimal and there was no shared mental model. Good Bridge Team Management relies on both mutual understanding and respect between the pilot and the bridge team.

It is entirely right and proper that the pilot’s actions are closely monitored and challenged. In return, the pilot should expect the full help and support of the bridge team. And bridge teams must expect they will also be closely monitored and challenged, and, in return, they should expect the full help and support of the pilot. Pilotage is not about us and them. It is a shared responsibility to achieve the common goal of safely navigating the ship through the pilotage district.

References:

- Article 182, Code of Public Maritime law. Legislative Decree 187/1973.

- Article 97, Merchant Shipping code of the Russian Federation.

- p.81, Minding The Helm: Marine Navigating and Piloting; National Research Council. 1994.

- American Pilots Association, 1997. Accessed americanpilots. org on 15 Feb 2019.

- p.461, Maritime Law, Hill; Routledge, 2003.

- NTSB Accident no. DCA16FM042 Celebrity Infinity June 3rd 2016.

- NTSB Accident no. MAB1706 Carnival Pride 8th May 2016.

- p.5, ‘The Navigator, Issue No 07, October 2014. NI/RIN.

- F v Westrenen, ‘The Maritime Pilot at Work’, unpublished doctoral thesis 1999.

10.’Modern Cruise Ship Bridge Operations’, p.28, Seaways, December 2018. Nautical Institute

11. ‘Bridge Team and Pilot Cohesiveness’, p.6, ‘Seaways’, July 2016, Nautical Institute

12. p.100, ‘A Guide to Good Practice on Port Marine Operations’, UK Dept of Transport, Feb 2018.

13. p.52, MAIB Report 23/2017. October 2017.

14. Osler, D. ‘CMA CGM Libra ruling raises bar on seaworthiness, WFW argues’, Lloyd’s List, 08 April 2019.

15. Cruise Market Watch, accessed cruisemarketwatch.com on 16 th Feb 2019.

’16. The Pilot’, NZMPA.

17. p.35, MAIB Report 12/2016, mv Hamburg.

18. p.1, MAIB Report 23/2009, mv Vallermosa.

One Response to “The Pros and Cons of the Con – Time to call a Truce”

Ultimately, it is the case law that prevails.

Pikeman